Why and what territories Armenia had to concede under the Treaty of Batum

13.06

2025

Part Four

On June 4, 1918, a peace treaty was signed between Armenia and Turkey. On the same day, an agreement was reached between the two delegations in Yerevan and Constantinople to exchange diplomatic and military representatives. In early August, Mehmed-Ali Pasha (of Bosnian origin) was appointed as the diplomatic and military envoy attached to the Government of the Republic of Armenia, while F. Takhtachyan was appointed in Ottoman Turkey.

The Treaty of Batum and articles related to it came into force upon signing; however, from an international law perspective, they did not possess legal validity because neither the Ottoman Empire nor the governments and legislative bodies of the Republic of Armenia ratified them. Moreover, they were not recognized by the members of the Quadruple Alliance, the Entente, Soviet Russia, and other countries.

The Treaty of Batum “operated” from June to November 1918, until the final defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I.

The treaty was signed in a formal ceremony on June 4, 1918. Its full name was “Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the Ottoman Imperial Government and the Republic of Armenia.” It was signed on behalf of the Turkish delegation by Halil Bey, Wehib Pasha, and on behalf of the Republic of Armenia by A. Khatisyan (head of the delegation), H. Kajaznuni, and M. Papajanyan.

On the same day, the Armenian delegation sent a telegram to Supreme Patriarch Gevorg V, stating that a treaty had been signed, hostilities had ceased, Etchmiadzin remained within Armenia’s territory, and Yerevan was the capital (from the very first days of existence, the First Republic of Armenia attached great importance to the Church). On the evening of June 4, at 5 p.m., a plenary session was held to sign the protocol of exchange and arrangements related to the Armenian-Turkish peace treaty and its three annexes. During the session, A. Khatisyan delivered a speech in Armenian, which he then translated into Russian and French. He particularly stated that Armenia “has long sacrificed many things to secure its right to exist as a nation. Today, it has openly gained this right and entered the ranks of independent states. This great day will become a solemn chapter in Armenian history… We are firmly convinced that our Armenian brothers who have left Turkey will soon be able to return there.”

After the protocols of the Armenian-Turkish documents were signed in Batumi on the early morning of June 5, the Armenian delegation returned to Tiflis. The Armenian National Central Council began forming the legislative (Armenian Council) and executive bodies of Armenia. Thus, the Treaty of Batum of June 4 is the first international document signed by the representatives of independent Armenia.

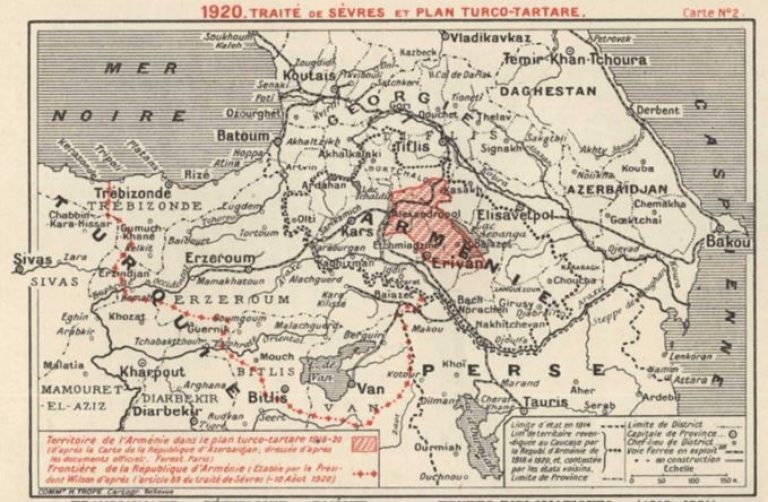

The main document consisted of 14 articles and three additional annexes. According to this treaty, not only Western Armenia but also a significant part of Eastern Armenia—Sharur-Daralagyaz, Nakhijevan, Surmalu, Kars, Kaghzvan, Sarighamish, and Lori—was ceded to the Ottoman Empire. Armenia was left with the province of Nor Bayazet, more than 11,000 square kilometers of the provinces of Yerevan, Etchmiadzin, Alexandrapol and Gharakilisa. It lost Alexandrapol and the railway line up to Jugha (Julfa). The republic was left with only a 13 km stretch of railway. Control over the railroads was transferred to Turkey, and the state border was established 7 km from Yerevan. Armenia lost 28,000 square kilometers with a population of 900,000. Under the Treaty of Batum, Georgia lost 10,000 square kilometers with a population of 350,000. Georgia’s territory was limited to Tiflis, Kutaisi, Gori, and nearby central regions. The Turks seized 20.6% of Transcaucasia and 18.5% of its population. In total, the Turks occupied 38,000 square kilometers of Transcaucasia, with a population of around 1.25 million.

During World War I, the struggle for Baku’s oil fields was between two allies—Ottoman Turkey and Imperial Germany—and since the shortest route to Baku passed through Armenia, the Turks, moving toward Baku, could not leave Armenian hostile armies behind. For this reason, the Ottoman Empire quickly recognized the independence of Armenia by signing the Treaty of Batum, thus securing its rear. Immediately after the conclusion of the treaty, Wehib Pasha demanded that the Armenian government immediately fulfill the obligations outlined in the treaty’s provisional annex, specifically the first article: “The Government of the Republic of Armenia will immediately begin demobilizing its troops. The number of these troops, as well as the military districts they will be part of, will be determined in coordination with the Ottoman Imperial Government for the entire duration of the war.”

Under Article 5 of the treaty, the Armenian government was obliged to actively prevent the formation and arming of any gangs within its territory, as well as to disarm and disperse any gangs that might attempt to hide there.

Additionally, Article 11 stipulated that the Armenian government would exert all efforts to evacuate all Armenian military forces from Baku after the signing of the treaty and ensure that this evacuation would not lead to any conflicts.

As we can see, the Armenian government was forced to assume a triple obligation: first, to disband the Armenian army, leaving only 1,200 soldiers—on the one hand, to end all military operations in the rear of the Turkish army, and on the other hand, which was much more important, to force the Armenian troops to withdraw from Soviet Baku.