When a state faces a dilemma — Lessons from December 2, 105 years later

02.12

2025

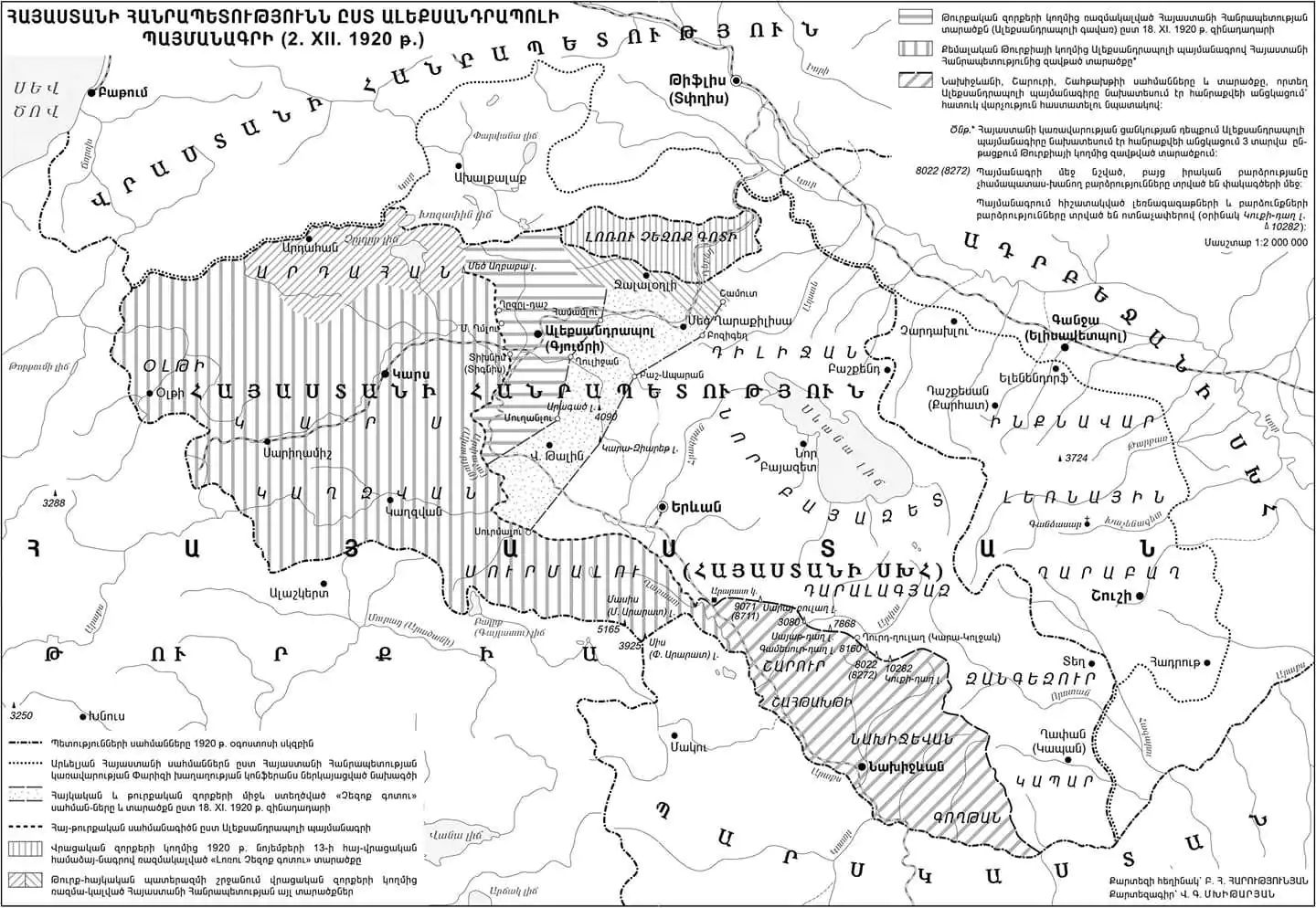

105 years ago, on Dec. 2, 1920, two pivotal treaties were signed in Yerevan and Alexandropol (Gyumri) within hours of each other, determining the political fate of the Armenian people and their newly independent state. These were the Armenian-Russian treaty signed in Yerevan and the Armenian-Turkish treaty signed in Alexandropol on Dec. 3. Both treaties were signed during the most turbulent period of the First Republic of Armenia, proclaimed in 1918.

Interestingly, It is noteworthy that a consensus has been formed around the criticism of the provisions of the Alexandropol Treaty both among those who promote pro-Turkish historical theses and among representatives of Soviet historiographical thought. While the first group argues that the First Republic of Armenia was destroyed to “fit Armenian state interests into Russian objectives,” Soviet historiography sees Armenia’s main foreign policy misstep as occurring in May 1920, when Yerevan refused Sovietization, instead placing its hopes in the diplomatic promises of the Entente allies.

Today, 105 years later, the Republic of Armenia faces a diplomatic dilemma, and any miscalculated step or decision could be decisive for the Armenian people and the sovereignty of the state. But what happened 105 years ago?

On Sept. 28, 1920—almost the same day marking the start of the 44-day war in Artsakh a century later—the Armenian army suffered defeat in its war with Turkey, under simultaneous attacks from Russian and Armenian Bolsheviks, Sovietized Azerbaijan (from April that year), and Kemalist Turkey. Although the Armenian army was fighting on four fronts, the causes of defeat were not solely military-strategic or tactical. Territorial losses, refugee crises, demoralized units, and economic and financial hardships plunged the country into a political crisis.

The situation imperatively dictated the resignation of the government defeated in the war, regardless of the reasons for the defeat, and the assumption of responsibility for the future of the country by new political forces. Therefore, on Nov. 23, the government of H. Ohanjanyan resigned, and was replaced by the “pro-Russian” government of S. Vratsyan, which lasted only 10 days. Taking into account the growing threat of Bolshevism, in order to stop the advance of Turkish troops and save the country, S. Vratsyan’s government began negotiations with Soviet Russia and Kemalist Turkey.

Negotiations with Turkey began in Alexandropol on Nov. 25, 1920. Initially, the Armenian side preferred not to negotiate directly with the Turks and suggested the Georgians act as intermediaries (if the Armenian side wanted to hold real negotiations with the Turks, as many are trying to claim, why did they resort to Georgian mediation instead of direct ones?). However, the Turks resolutely rejected Mdivani’s mediation, sharply demanding that the negotiations be held face to face, only between Armenians and Turks. In that situation, there was no alternative and the Armenian side was forced to agree to Turkey’s proposal-demand. Despite the Alexandropol talks, the core issue remained relations with Russia, which presented two main demands:

- Sovietization of Armenia

- Entry of two Red Army divisions into Armenian territory

The Soviet side appointed Armenian B. Legran to negotiate with S. Vratzian, Armenia’s fourth and last prime minister. It soon became clear that even Armenia’s pro-Russian socialist government could not become a strategic ally of Soviet Russia and ensure the independence of the Republic of Armenia. Legran demanded complete abandonment of the Treaty of Sèvres and reliance solely on Soviet Russia. It was a very difficult situation, because B. Legran also proposed to allow the transportation of Soviet troops and ammunition to Turkey via Armenian railways, to submit the issue of resolving border disputes with neighboring states to Russian jurisdiction, to recall from Alexandrapol the delegation of A. Khatisyan negotiating with the Turks, and to introduce Russian troops into Armenia.

The Armenian government decisively rejected the first demand but accepted the others. A draft treaty of 17 articles was prepared. The Armenian side demanded guarantees in return for all this, but the surprising thing was that even in return for all this, B. Legran did not give any guarantees that in the event of such a step, the Turks would not move from Alexandrapol to Yerevan and would not occupy other territories of the country. The situation forced the Armenian government to continue negotiations in Alexandrapol, trying to stop the Turks’ advance. The Turks, in turn, understanding the situation well, adopted a very uncompromising position and spoke in the language of ultimatums. While this was happening in the west of Armenia, Russia in the east also resorted to open diplomatic pressure—again speaking in the form of ultimatums.

The political situation became particularly unbearable when, on Nov. 29, Legran presented an ultimatum to Armenia, in which he declared that the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party had decided to establish Soviet rule in Armenia, and presented a written demand.

Prior to the ultimatum, in mid-November, Soviet Russia had formed a Revolutionary Committee of Armenia (HayHeghKom) in Baku under Sargis Kasyan, who would later be shot in 1937 by fellow Bolsheviks. On Nov. 29, under the leadership of the Revolutionary Committee, the Armenian Bolsheviks, accompanied by a Red Army unit, attacked Armenia from the east and entered the village of Ijevan from Azerbaijan, where, in a declaration published on the same day, it was announced on behalf of the workers’ and peasants’ uprising—which, in reality, had not taken place— that the “Dashnaktsutyun government” had been overthrown, and Armenia was proclaimed a Soviet Socialist Republic. The next day, the Bolshevik Revolutionary Committee of Azerbaijan, headed by N. Narimanov issued a statement defending Soviet Armenia, while simultaneously declaring that in favor of Soviet Armenia, it was renouncing its claims to Zangezur, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Nakhijevan.

Faced with Turkish military pressure on one side and inevitable Sovietization on the other, the Armenian government had to choose between Russia and Turkey. Preference was given to Russia. Until Russian forces arrived in Yerevan, Armenian authorities, led by A. Khatissian, began peace negotiations with Turkey to halt its advance from Alexandropol and buy time.

Negotiations in Yerevan, beginning Nov. 30 between Legran and Armenian pro-Russian ARF representatives Dro and H. Terteryan, concluded on Dec. 2 at noon with a 17-article treaty. Key points included:

- Armenia was declared an independent Soviet Socialist Republic.

- Soviet Russia recognized the entire Yerevan province, part of Kars province, Zangezur, part of Ghazakh district, and those territories of Tiflis province that were part of Armenia on Sept. 28, 1920, as indisputable territories of Soviet Armenia.

- The border between Armenia and Azerbaijan was to be determined by a conference of their representatives with RSFSR participation; if no agreement was reached, a referendum would be conducted.

- Russia was obligated to deploy military forces to defend the Armenian SSR.

- The Soviet side agreed not to hold Armenian army officers accountable for past actions or persecute members of the ARF and those from other socialist parties (social democrats, etc.).

- The HeghKom would include five Bolsheviks and two left Dashnak members.

Before the HeghKom arrived in Yerevan (from Ijevan on Dec. 4, as the Armenian government offered no resistance), authority was under the command of the Red Army led by Dro, with RSFSR commissar O. Silin attached.

Thus, Armenia’s peaceful Sovietization was the result of the Armenian government’s decision to reach an agreement to avoid civil war, not a genuine workers’ uprising. A treaty was signed, and the Armenian government peacefully transferred power to the Bolsheviks. However, before the ink had dried on the agreement, the Bolsheviks violated it, refusing to include left Dashnak representatives in the Revolutionary Committee and soon initiating repression against former Armenian army officers.