Armenia ‘between the Bolshevik hammer and the Turkish anvil’: How the Alexandropol Treaty was signed

09.12

2025

Part Two

At the same time, the Turkish delegation in Alexandropol presented very strict demands to the delegation of Alexander Khatisian. When Khatisian reported these demands to Vratsyan, he was instructed: do whatever you need, but buy as much time as possible. The Armenian delegation, by gaining time, signed the Alexandropol Armenian-Turkish Peace Agreement on December 2 into December 3 (at 2 a.m.), 14 hours after the treaty between Armenia and Russia had been signed in Yerevan—by which time authority had already been transferred to the communists, and the Alexandropol agreement had lost any legal force.

While the treaty was humiliating for Armenia, the Armenian delegation succeeded in delaying Turkish advances, understanding that the Alexandropol Treaty would never be implemented. It was signed between the outgoing Armenian government and the government of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. On the Turkish side, it was signed by the commander of the Turkish army, Kâzım Karabekir; on the Armenian side, by Alexander Khatisyan. The treaty consisted of 18 articles in French and Turkish.

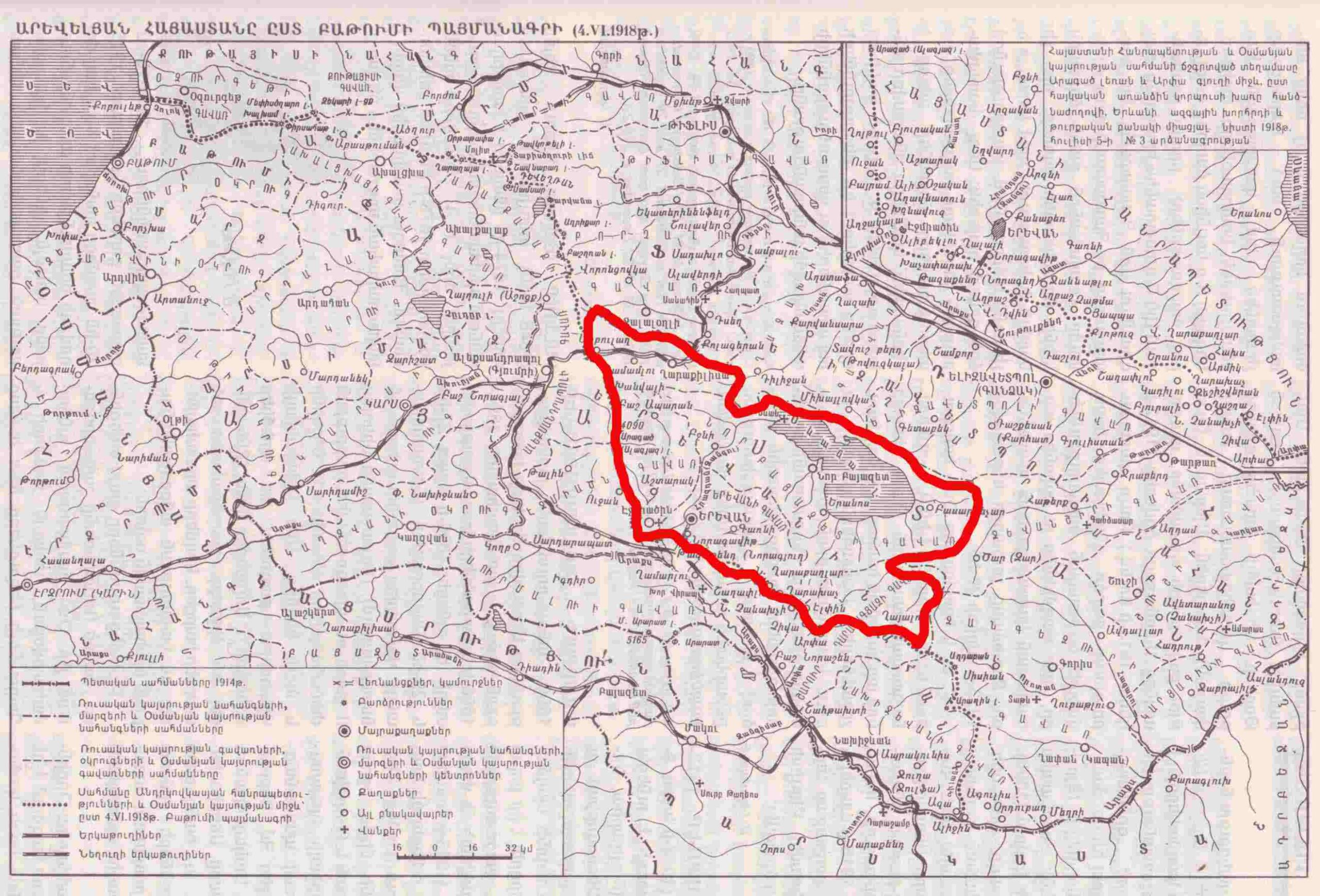

Under the treaty, Armenia’s territory was limited to roughly 12,000 square kilometers, primarily covering the Yerevan area and part of Shirak. The entirety of Nakhijevan, Artsakh, Syunik, a large part of Lori, significant parts of Tavush, and Gegharkunik, and most of Lake Sevan’s basin were ceded. Turkey gained the Kars province and Surmalu district—including Mount Ararat—and parts of Western Shirak up to the midstream of the Akhuryan River and Ardahan. The Sharur and Shahtakhti districts were temporarily under Turkish protection, with their future status to be decided by referendum. Armenia was deprived of the right to maintain a conscription-based army; its armed forces were limited to 1,500 soldiers, eight cannons, and 20 machine guns. Turkey was obligated to provide military assistance to Armenia in the case of internal or external threats, upon the Armenian government’s request. The Alexandropol Treaty was to be ratified one month after signing.

According to Kâzım Karabekir’s memoirs (Kâzım KarabekirPaşa’nın Hatırâtı/ İstiklâl Harbimiz), the documents show that the Turkish commander was precisely aware of Soviet troop movements and accelerated negotiations due to escapes and military advances. The chronological overlap of negotiations between Drou-Legran and Khatisyan-Karabekir was not accidental. Turkish historiography does not provide evidence that the Turks signed the treaty knowing that Armenia had already been Sovietized and that the Alexandropol Treaty had no legal validity. The Turkish delegation was aware, at least, of Bolshevik military-diplomatic activity but did not have intelligence confirming that Armenia had already been Sovietized.

Later, the Alexandropol Treaty was replaced by the Moscow Treaty of March 16, 1921, and the Kars Treaty of October 13, 1921. The new Bolshevik Armenian government annulled the legally non-binding Alexandropol Treaty. What were the main grounds for its illegitimacy?

- The treaty was signed under the open threat of force, violating international law, whereas under international law, parties should act without coercion.

- On December 4–5, 1920, the new Bolshevik authorities officially declared that they did not recognize the Alexandropol Treaty. In other words, it was rejected by Armenia’s legitimate government within days of signing.

- The 1921 Moscow and Kars treaties replaced the Alexandropol Treaty. Under international law, if a new treaty replaces a previous one, the prior document loses legal force. Even if Alexandropol had been “legally authorized”—which it was not—it would have ceased to exist within months.

Thus, the Alexandropol Treaty was neither legal, nor sovereign, nor binding.

Historians have described this period, in the words of Vratsyan, as the time when Armenia was “between the Bolshevik hammer and the Turkish anvil.” Unable to withstand the pressure of powerful external forces, aggressive neighbors, and cooperation with Armenian Bolsheviks, the First Republic of Armenia fell after two and a half years of struggle.

Nevertheless, the First Republic of Armenia fulfilled its historic mission, paving the way for a Second Republic with limited sovereignty, and later, for its successor—the independent Third Republic of Armenia.